The psychology of money and how it influences us

Author

Josh Pigford

Money. It’s what makes the world go round. But what is it? According to the definition of money, it serves as a medium of exchange or a verifiable record accepted as payment for goods and services or as repayment for debts owed.

Money has existed for millennia across different cultures and regions. Still, many people don't know how money works, how it affects our behavior, or how our brains psychologically affect our relationship with money. Understanding this relationship can be the difference between you hitting your financial goals or failing to do so, as the principles of money are fundamental in nature.

Knowing how money affects your brain and decision-making can help you save more, budget appropriately, and become a more well-rounded and disciplined investor.

Your brain on money

The field of behavioral finance teaches us that humans are not always rational actors that take the most optimal, data-backed decision in any given circumstance. These deviations from rationality (called cognitive biases) become more exacerbated when it comes to money. A couple of examples of how our brains react to the concept of money and how we interact with it are given below.

1. Mental accounting:

In a study conducted in 1983, Kahneman & Tversky used the concept of “mental accounting,” where people keep separate mental accounts for budgeting and expenses, which may lead to irrational decision-making. In simple terms, even though every dollar is indistinguishable from the next, people classify them differently, which doesn't lead to the most optimal financial outcomes.

The example below was used in the study referenced above by Kahneman and Tversky to help understand the concept and validity of mental accounting.

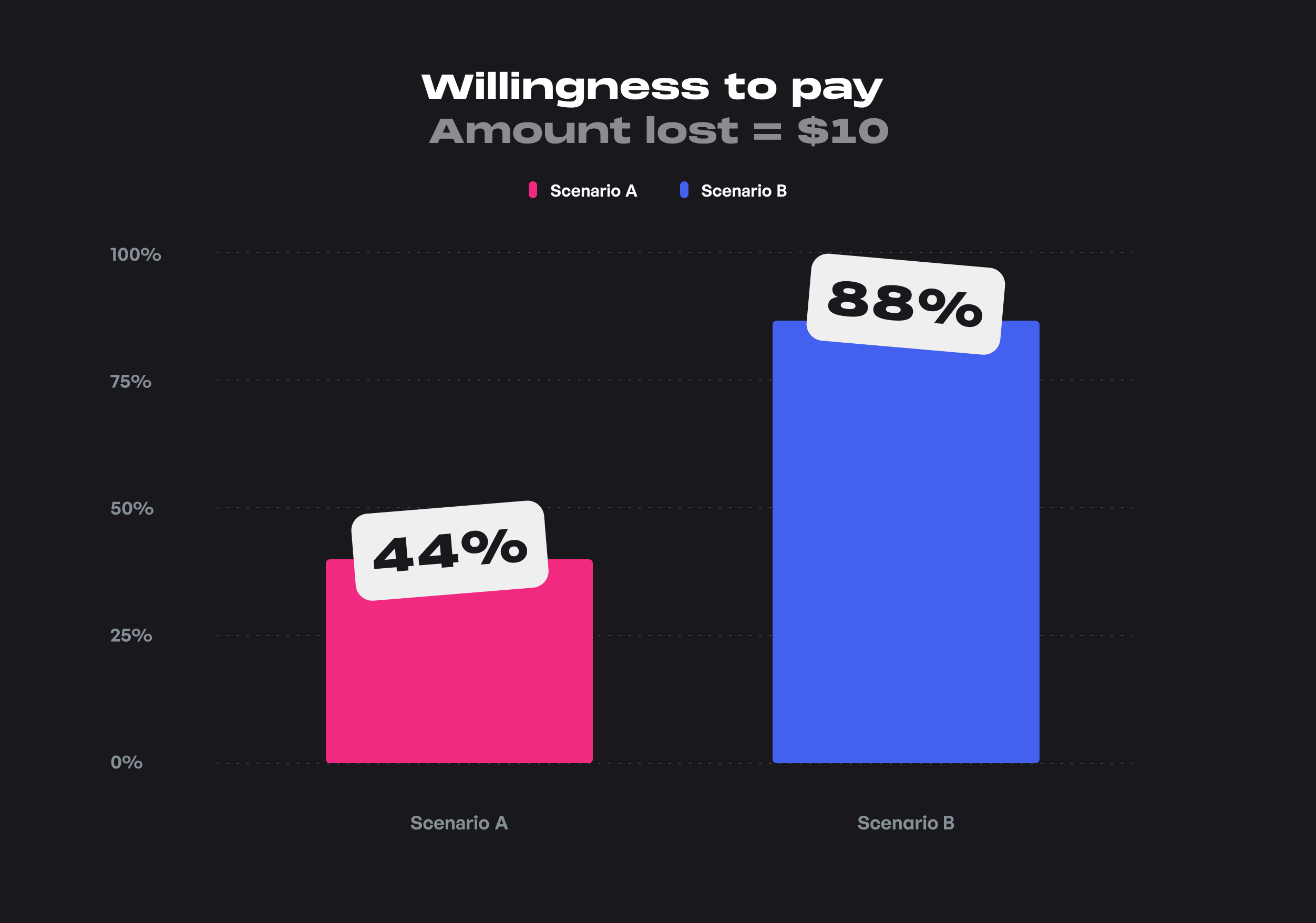

Imagine you just arrived at a theatre, and as you reach into your pocket to pull out the $10 ticket you purchased in advance, you discover that it’s missing. Would you fork over another $10 to see the movie? Compare that to a second scenario in which you did not buy the ticket in advance, but when you arrive at the theatre, you discover you had lost a $10 bill on the way. Would you still buy a movie ticket?

This experiment by Kahneman & Tversky showed that though the amount you lost is $10 in both instances, people were twice as likely to buy a ticket in the second scenario (88%) than in the first scenario (44%).

In the first scenario, the mental budget spent on the movie had doubled, but in the second case, the person did not allocate the lost cash to the movie budget, so people were more likely to buy a ticket.

We can also observe this phenomenon during windfall gains such as surprise bonuses, lottery wins, and cash from friends and family. This money, although fungible, is more likely to be spent faster as it is contained in a separate mental account kept for windfall gains.

A straightforward way to overcome mental accounting is to consider all the money you receive as fungible (indistinguishable from one another) and maintain a dynamic mental account. For example, if your mental account for your investments is 30% of your income, and you receive a bonus this month, ensure that you increase the percentage allocated towards investments for that particular month. This is because the dollar amount you allocate towards expenses will be relatively similar from month to month.

Also, segregating your money for specific purposes can help reduce unnecessary spending in different categories, especially “wants.” For example, suppose you have mental budgets for different budgeting categories such as investing, needs (your basic necessities) and wants (purchases that improve your quality of life). In that case, it makes it tougher to overspend as a budget is locked for each category. You can go further and have different checking accounts dedicated to each category to maintain allocations between different categories appropriately.

2. The pain of paying:

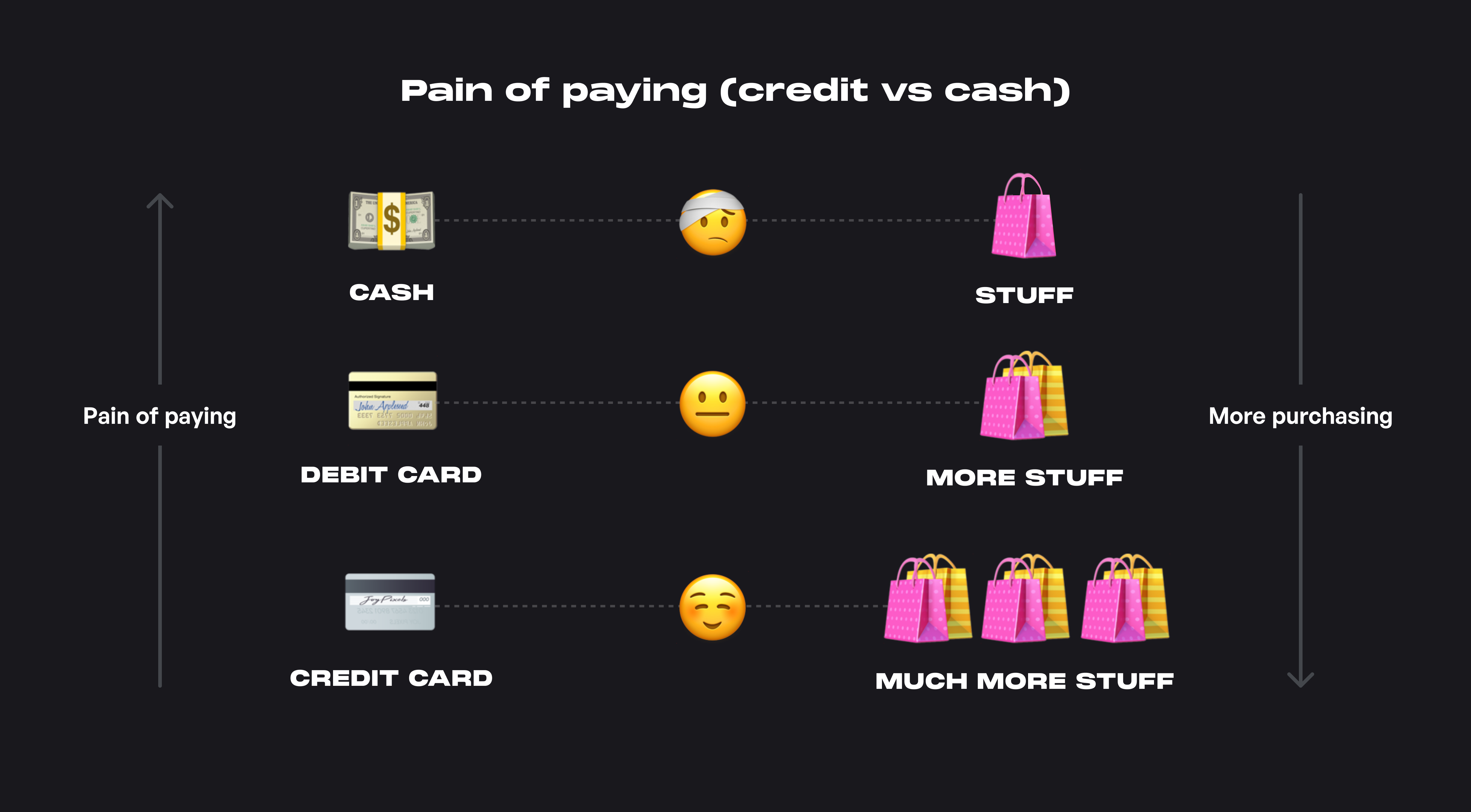

Do you find yourself spending more when you use credit cards when compared to cash? You’re not alone.

Researchers at MIT conducted an experiment in 2001 to see if people were more willing to pay if they used credit cards instead of cash. They set up a sporting event where the tickets were auctioned off to the highest bidders, and the only available forms of payment were via credit cards or cash. The findings showed that bidders who used credit cards were willing to pay twice as much for a ticket as those who wanted to purchase a ticket with cash.

This deviation from rationality occurs because the consequences of the action are pushed towards the future if you use a credit card. The “future you” must deal with the issue, not the “present you.”

However, when you pay with cash, you feel the pain of getting separated from your money , and the “present you” is affected. This concept was confirmed in 2016 when Nina Mazar and colleagues found that parting with cash activated pain processing regions in the brain and reduced the willingness to pay.

The reverse happens with using credit cards, as they encourage and even reward you for spending. We also don't observe the process of money disappearing (it’s not your money in the first place, which causes mental accounting problems), making money less tangible. Studies on the subject also showed that paying with credit cards significantly reduced the pain of paying and led users to make more risky financial decisions.

One way to overcome the issue of overspending is to increase the pain of payment while making purchases. Try to use cash wherever possible and avoid using credit cards regularly, increasing the pain of payment and restricting unnecessary spending.

The above examples show how money influences our brains psychologically and the different cognitive biases regarding money. Our relationship with how we view money and interact with it is vital in how we spend, save, invest and achieve our financial goals.

Following principles such as mental accounting can help you segregate your financial goals into individual buckets and manage them appropriately. Whereas principles like the pain of paying can help reduce unnecessary costs and prevent overspending to a large extent to put you on the right track towards hitting those goals.

Three lessons from the book - The Psychology of Money

When we want to learn about the relationships our brain has with money and how money influences our daily decisions, there is no better book than Morgan Housel’s _ The Psychology of Money _.

In this book, the author, in the form of several short stories, shows you how different people think about money and how you can better understand one of the most essential topics that drive our daily lives.

1. Luck and risk:

Luck and risk are both the reality that every outcome in life is guided by forces other than individual effort. They are so similar that you can’t believe in one without equally respecting the other. They both happen because the world is too complex to allow 100% of your actions to dictate 100% of your outcomes.

Especially in the financial world, it is almost impossible to quantify the role of luck in decision-making and investment outcomes. Good decisions can lead to bad outcomes, and bad decisions can lead to good outcomes sometimes.

Just understand that there may not be much difference between the top 10% and the bottom 10%. The only thing differentiating the two could be that the top 10% benefited from luck while the bottom 10% became victims of risk.

2. The power of compound interest:

If something compounds—if a little growth serves as the fuel for future growth— a small starting base can lead to results so extraordinary they seem to defy logic. It can be so logic-defying that you underestimate what’s possible, where growth comes from, and what it can lead to.

We all know how rich Warren Buffet is, but did you know that he attained 97% of his wealth after the age of 65? Our minds cannot comprehend the power of compounding over long periods.

However, for compounding to show its magic, you should let it go uninterrupted for long periods of time. The hallmark of a great investor is having a long time horizon to make compounding work for them.

3. Personal experience <<< World’s experience

Your personal experiences with money make up maybe 0.00000001% of what’s happened in the world, but maybe 80% of how you think the world works.

If you started investing during the historic bull run of the last decade (2008-2021), then stocks might seem like the only asset you need to invest in. However, if you bought stocks before any crisis, such as the Great Depression, the dot-com bubble, the 2008 financial crisis, etc., you would be opposed to investing in stocks.

The time period you were born in and the information you consume is vital in how you view different asset classes. So whenever you’re planning out your investment portfolio, make sure that you look at the historical performance of asset classes over long periods to get a clearer picture of asset risk and returns.

You can learn in-depth about the topics discussed above by either getting the book or checking out this article by sloww.co, which has about 18 lessons from the book.

Key takeaways

- In this article, we started by understanding the definition of money - which is to serve as a medium of exchange that is valuable and accepted in exchange for goods or services rendered.

- Then, we moved on to how our brains react to the concept of money and how money affects the way we spend, save, and invest on a psychological level. We take two widespread mistakes we make in the form of mental accounting and the pain of paying to help you understand your relationship with money.

- Finally, we understood certain money principles from _ The Psychology of Money. _ We went deeper into three principles (Luck vs. risk, compound interest, and experience) that can help you better understand money and how we interact with it.

Comprehensive Financial Planner: Maybe's Expertise in Managing Your Finances

Josh Pigford

Understanding money and its history

Josh Pigford

11 bold ways to boost your financial health

Josh Pigford

Join the Maybe  waitlist

waitlist

Join the waitlist to get notified when a hosted version of the app is available.